ARE BITCOINS USED ON THE DARK WEB

QUEM TEM MAIS BITCOINS NO MUNDO

IPHONE BITCOIN WALLET

Vít Macháček and Martin Srholec

Think-tank IDEA of the Economic Institute of Czech Academy of Sciences

Study No. 6/2019

May 2019

Science knows no limits or borders. Scientific inquiry has therefore gone global long before the economy or culture. Nevertheless, this does not necessarily mean that science is global to the same extent everywhere.

To what extent are scientific outputs published in global as opposed to local journals? How does this differ across countries and disciplines? How much has this changed over the last decade?

The aim of this study is to show that. We provide new evidence on the globalization of science that allows us to compare over space, fields and time. Specifically, we compare 174 countries and various country groups in 4 broad and 27 narrow disciplines over the period from 2005 to 2017.

The study is based on six journal-level indicators of globalization. The benchmark indicators are derived from the data on authors by the country of origin. For comparison, we also use data on documents by the country of origin and English-written documents.

The journal-level indicators are then aggregated to countries and disciplines. These results are standardized between 0 and 1, in which 0 refers to the lowest and 1 to the highest globalization.

The analysis is based on data from the Scopus citation database. The list of journals and assigned disciplines is obtained from the gateio.

Globalization of science should not be confused with quality (or relevance) of science; they are likely to be related in many ways, depending on the discipline, but they are different phenomena.

The results are presented in an interactive manner that allows readers to customize the analysis. Further, the results should be of interest not only to academics, but also to policy-makers and to a broader audience across the globe.

Please see this link here for earlier studies by the IDEA think tank on related topics, including on local journals, predatory publishing, and quantity vs. influence of academic publications.

Each point depicts the globalization index $G^S_{c,d,y,i}$ of a respective country and discipline in a given year and indicator. For more details see the definition of the journal-level indicators and aggregation procedure.

Use the upper dropdown menus to customize the output. One can compare either:

The main dimension is fixed by the button . Up to

10 items can be included in the comparison.

You may move the text windows by dragging the button

in the top-left corner.

Science in advanced countries has traditionally been globalized.

In contrast, transition countries continue to be relatively isolated.

Developing countries remain in the middle and close to the world average.

Interestingly, there does not seem to be much change here.

Tip: Display the discipline of your interest using the upper menu. For the definition of country groups see the note below the figure.

Not surprisingly, the Unites States, jointly with the EU-28, set the upper standard, followed by Japan.

China scores last initially, but then globalizes its science base enormously, eventually converging to a similar level as Brazil and India.

Russia starts and remains low, lagging increasingly behind the rest of the pack.

Tip: Add (or remove) countries (or country groups) using the upper menu. Replace the EU-28 average by individual member countries of your interest.

Not only Russia, but also other former members of the Soviet bloc, cluster at the bottom of the worldwide ranking.

Chinese science in fact turns out to be the least globalized in the whole world initially.

Tip: Replace China by other former members of the Soviet bloc to see how they fare in comparison to the world average.

In advanced countries, science is, on average, highly globalized across disciplines.

Physical and Life Sciences are the most globalized. Health Sciences rank even below Social Sciences, though the differences are very small.

In fact, it is difficult to find a sub-discipline that deviates significantly from this narrow corridor.

Tip: Add the sub-disciplines of your interest using the upper menu. For the definition of disciplines, see the note below the figure.

Russian science does not ever break from its inward-looking Soviet past, regardless of the discipline.

Russian Physical and Life Sciences remain significantly less globalized than elsewhere in the world.

The only major exception is the sub-discipline of Pharmacology, Toxicology and Pharmaceutics.

Interestingly, in many disciplines this is in a sharp contrast to the relatively high share of documents published in English.

In fact, about four-fifths of documents with at least one author from Russia were written in English over this period.

Tip: Display results for a different indicator using the upper menu.

China has profoundly globalized its science system, gradually moving from the lowest globalization rates to prominence on the world stage.

Chinese Social Sciences have become even more globalized than other broad disciplines and have already caught up with the EU-28 and the world average.

In some sub-disciplines, China has already surpassed the United States and is steaming forward to the top ranking.

If the trend continues, China will soon eliminate the gap with advanced countries in most of the sub-disciplines.

Tip: Compare the results for Hong Kong using the upper menu (the results for China do not include Hong Kong, which continues to be reported separately by Scopus).

In Western Europe, Social Sciences are highly globalized, as are Natural Sciences.

In Central (and Eastern) Europe, however, Social Sciences continue to maintain their own local publication silos.

The prime exception is Hungary, where Social Sciences used to be more oriented to the West even before the fall of the Berlin Wall.

Tip: Add other transition countries (or the group average) to the comparison using the upper menu.

Czechia is a prime example of a formerly advanced country that have been tarnished during the communist era.

Physical and Life Sciences have continued to be connected to the global arena.

Social Sciences have been locked behind the Berlin Wall; they steadily globalize, but from a low base, and there is still a long way to go.

Tip: Explore other countries of the former Soviet bloc using the upper menu. Note, for instance, the development in Ukraine.

Globalization of science provides a new perspective on the scientific landscape, which deepens what we know from standard bibliometrics in many respects.

The traditional science powerhouses in the North and West remain strong and at the core of the global system; highly interconnected and as globalized as ever.

In many countries of the former Soviet block, the low globalization of science is a symptom of a systemic failure; of science that is out of sync with the rest of the world and is inefficient.

After the fall of the Berlin Wall, it was understandable that science in transition countries would need time to catch up. In many disciplines, new infrastructure had to be built from scratch. However, three decades on, there is no longer any excuse.

China shows that where there is a will, there is a way. In little more than a decade, Chinese science has moved from relative isolation to the front pages of global journals amid an enormous expansion in size.

Other developing countries also allocate increasing resources to science and run the risk of creating ecosystems of local publishing similar to transition countries, or worse, e.g. falling for predatory journals.

Globalization of science that is pervasively lower than in similar countries should be a cause for concern, as it suggests that the science system has gone astray and needs an overhaul of its evaluation and funding framework.

More research is needed to better understand globalization of science. Does globalization of the national science system go hand in hand with quality and impact? Are there spillovers outside of the realm of science? What can be done about it?

Tip: Spend more time with the interactive app to explore the position of the country and discipline of your interest.

See full list of references

Recommended citation: Macháček, V. and Srholec, M. (2019) Globalization of Science: Evidence from Authors in Academic Journals by Country of Origin. IDEA Study 6/2019. Institute for Democracy and Economic Analysis (IDEA), CERGE-EI, Prague.

Acknowledgement: Financial support from the research programme Strategy AV21 of the Czech Academy of Sciences is gratefully acknowledged. All usual caveats apply.

Note: This study represents only the views of the authors and not the official position of the Economics Institute of the Czech Academy of Sciences or the Center for Economic Research and Graduate Education (CERGE), Charles University.

In this study, we analyzed local academic publishing in selected European countries over the 2013-2016 period.

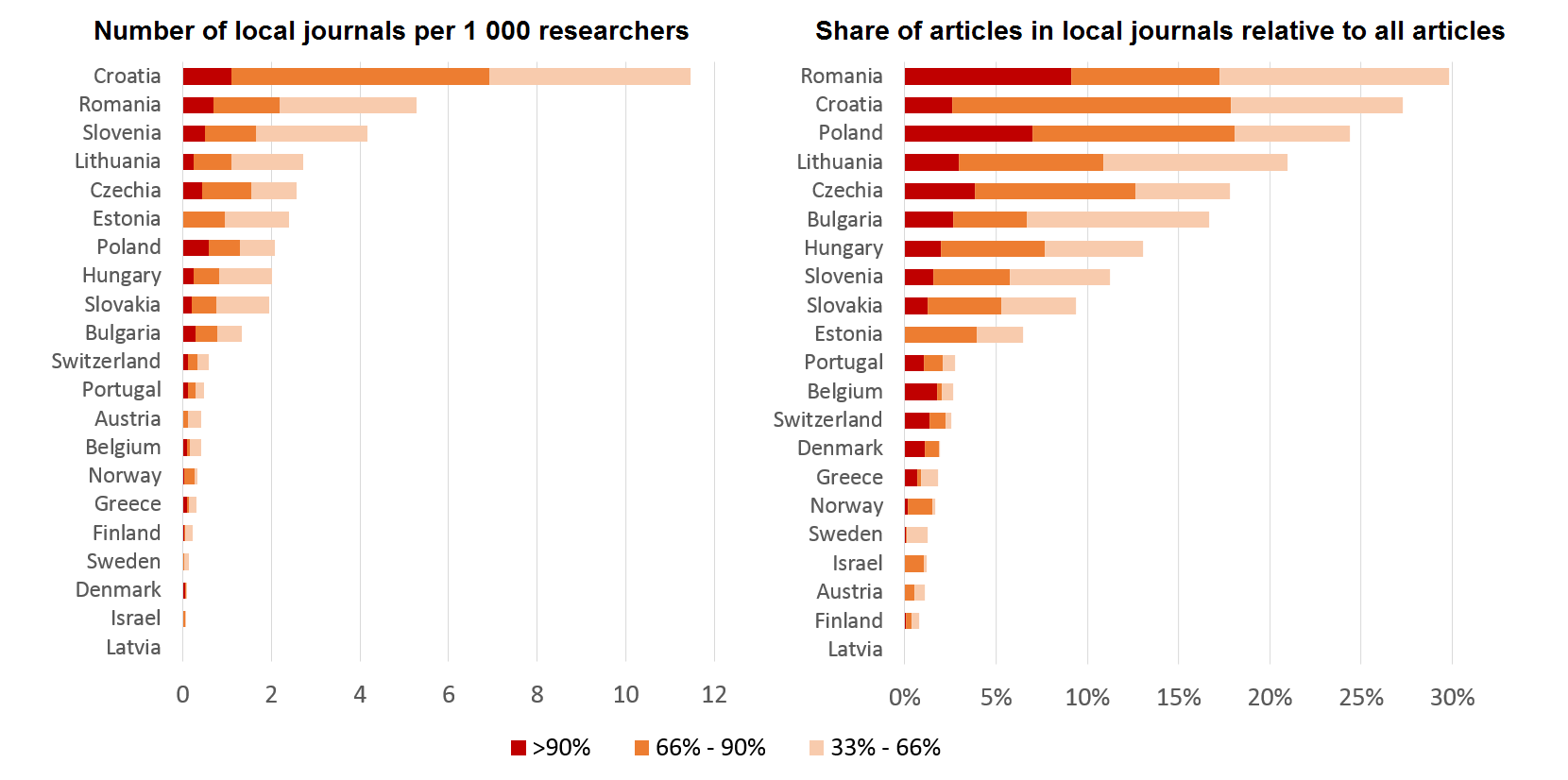

The results reveal a strong tendency to publish locally in the former communist countries. Local journals are prevalent in Croatia, Romania, Slovenia, Lithuania, and Czechia, but are rather rare in comparable advanced countries.

In Czechia, for instance, nearly one fifth of all indexed results are concentrated in Czech journals, with a high percentage (>33%) of articles by domestic authors. About half of authors contributing to Czech journals are based in Czechia, and another tenth in Slovakia.

In contrast, the vast majority of articles that appear in journals published in comparable advanced countries are written by foreign authors. The publishing of local, or at best regional, journals appears to be a distinctly Eastern European phenomenon.

Macháček, V. and Srholec, M. (2017) Local Journals in Scopus (only in Czech). Institute for Democracy and Economic Analysis (IDEA), Study 17/2017.

In this study, we mapped patterns of predatory publishing across the globe over the 2015-2017 period.

The analysis is based on Beall's lists of "potentially predatory" journals and publishers, of which we found 3,218 journals in Ulrichsweb and 405 journals in Scopus.

The results show that predatory publishing has become most widespread in middle-income countries in Asia and North Africa.

However, the analysis also indicates that Beall’s lists need to be used with caution, as some of the implicated journals may not be necessarily fraudulent in the strict sense.

Macháček, V. and Srholec, M. (2016) Predatory Journals in Scopus. Institute for Democracy and Economic Analysis (IDEA), Study 2/2017.

The study compares quantity and influence of publication output of countries in Web of Science (WoS) by category over the 2012-2016 period.

The quantity is given by the number of scientific articles and the influence is inferred from Article Influence Score (AIS) of the journals they are published in.

For each WoS category, the output and influence of the country is benchmarked relative to the chosen set of other countries.

The results reveal that both the size and influence of research in most Central and Eastern European countries continue to lag behind Western Europe.

This gap is especially strong in Social Sciences, Medical and Health Sciences, and Arts and Humanities

See the interactive application.

Jurajda, Š., Kozubek, S., Münich, D. and Škoda, S. (2017) Scientific publication performance in post communist countries: still lagging far behind. Scientometrics, 112(1). p. 315-328

Aman, V. (2016) Measuring internationality without bias against the periphery, Proceedings of the 21st international conference on science and technology indicators, p. 1042-1050.

Buela-Casal, G., Perakakis, P., Taylor, M. and Checa, P. (2006) Measuring internationality: Reflections and perspectives on academic journals, Scientometrics, 67(1), p.45-65.

IMF (2003) World Economic Outlook (Statistical Appendix; pp. 163-169).

Jurajda, Š., Kozubek, S., Münich, D. and Škoda, S. (2017) Scientific publication performance in post communist countries: still lagging far behind. Scientometrics, 112(1). p. 315-328

Macháček, V. and Srholec, M. (2016) Predatory Journals in Scopus, Institute for Democracy and Economic Analysis (IDEA), Study 2/2017.

Macháček, V. and Srholec, M. (2017) Local Journals in Scopus (only in Czech). Institute for Democracy and Economic Analysis (IDEA), Study 17/2017.

World Bank (2018) How does the World Bank classify countries? (version of June 2018). Accessed on March 15th 2019.

Zitt, M. and Bassecoulard, E. (1998) gate io, Scientometrics, 41(1–2) 255–271.

Zitt, M. and Bassecoulard, E. (1999) gate.io, Scientometrics, 46(3) 669-685.

Scopus Source List (April 2018 version) provided International Standard Serial Numbers (ISSNs), classification by disciplines, and publisher’s domicile of 34,964 academic journals.

In August 2018, detailed data on authors by the country of origin and language of documents in these ISSNs were downloaded from the Scopus citation database over the period from 2005 to 2017.

Only the following document types are included in this analysis: journal articles, reviews, and conference papers, i.e. so-called “citable documents”.

The following Scopus API request was used to download the data:

ISSN(AAAA-BBBB) AND DOCTYPE(AR OR RE OR CP) AND PUBYEAR = YYYY

in which AAAA-BBBB is the journal's ISSN and YYYY is the year.

Of 240 countries and territories, for which at least some information is available, we have excluded entities that are either dependent territories, too small, and/or with too few data to derive reliable results.

The resulting sample consists of 174 countries, including a large number of developing and transition countries, which together cover the overwhelming majority of the world's population and research output.

Data with "undefined" country origin of authors (about 5% of observations) has been excluded from the analysis. Data for Yugoslavia before 2007 were added to Serbia.

Advanced countries: Australia, Austria, Belgium, Canada, Cyprus, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hong Kong, Iceland, Ireland, Israel, Italy, Japan, Liechtenstein, Luxembourg, Monaco, Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Portugal, Singapore, South Korea, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Taiwan, United Kingdom, United States.

Transition countries: Albania, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Croatia, Czechia, Estonia, Georgia, Hungary, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Latvia, Lithuania, Macedonia, Moldova, Mongolia, Montenegro, Poland, Romania, Russia, Serbia, Slovakia, Slovenia, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, Ukraine, Uzbekistan.

Developing countries: Rest of the world.

Source: IMF (2003) World Economic Outlook (Statistical Appendix; pp. 163-169).

High income, Upper middle income, Lower middle income and Low income depending on Gross National Income (GNI) per capita in US dollars (Atlas methodology).

Source: World Bank (2018) How does the World Bank classify countries? (June 2018 version).

Europe, North America, South America, Central Asia, Middle East, East Asia, South Asia, Pacific, North Africa, Sub-Saharan Africa based on geography and administrative borders.

Source: World Bank (2018) How does the World Bank classify countries? (June 2018 version).

EU-15: "Old" EU member countries (before 2004).

EU-13: "New" EU member countries (accession between 2004 and 2018).

EU-28: EU-15 and EU-13 combined.

OECD: OECD member countries (as of January 2019).

According to the Scopus Journal Classification journals are classified into the following 4 broad subject clusters:

which are further subdivided into 27 major subject areas, such as:

1.1 Agricultural and Biological Sciences,

1.2 Biochemistry, Genetics and Molecular Biology,

1.3 Immunology and Microbiology,

1.4 Neuroscience,

1.5 Pharmacology, Toxicology and Pharmaceutics,

etc.

If a journal is assigned to multiple categories, it is fully counted in each of them.

The Scopus Source List is a source of journals.

Both active and inactive academic journals with ISSN are considered. We downloaded 34 965 ISSNs for each year from 2005 - 2017.

Only articles, reviews and conference papers are included in this analysis.

The following Scopus API request was used to download the data in August 2018:

ISSN(AAAA-BBBB) AND DOCTYPE(AR OR RE OR CP) AND PUBYEAR = YYYY

where AAAA-BBBB is the journal's ISSN and YYYY is the year.

Following Zitt and Bassecoulard (1999), the evidence from journals is aggregated to the level of countries and disciplines.

The aggregated figures are calculated as an average of the journal-level indicator weighted by the journal's share on the country's total documents in the respective discipline.

Only the results of the aggregation procedure based on data from at least 30 journals are reported.

Globalization of science in the country $c$, discipline $d$ and year $y$ measured by the indicator $i$ is calculated as follows:

$$ G_{c,d,y,i} = \sum_{j=1}^{J} a_{c,d,y,j} g_{j,d,y,i}(.) $$$a_{j,c,d,y}$ is the share of documents with authors from the country $c$ in journal $j$ on all documents of the country $c$ in discipline $d$ in year $y$.

$g_{j,d,y,i}$ is the globalization indicator $i$ of journal $j$ in discipline $d$ and year $y$.

Subsequently, the aggregated globalization index was standardized between $0$ and $1$ and converted to an ascending scale to simplify the interpretation of the results:

$$ G_{c,d,y,i}^S = \frac{G_{c,d,y,i} - G_{i}^{min}}{G_{i}^{max} - G_{i}^{min}} \alpha_i $$in which $G_{i}^{min}$ and $G_{i}^{max}$ is the minimum and maximum value of the indicator $i$ across all years, countries, and disciplines and $\alpha_i$ equals $-1$ for the minimizing indicator (i.e. low values for high globalization) and $1$ otherwise, as the results of which $0$ refers to the lowest and $1$ to the highest globalization.

The methodology builds on the pioneering work of Zitt and Bassecoulard (1998), which we complement with the contributions by Buela-Casal et al. (2006), Aman (2016) and two indicators of our own.

In essence, the most globalized journals have a structure (of documents by the country of origin of authors, etc.) that closely resembles the global structure of the whole discipline and vice-versa.

Only journals with at least 30 documents in the particular year are included in the calculation.

$N_{c,j,y}$ and $N_{c,d,y}$ is the number of documents with authors affiliated to the country $c$ in journal $j$ and discipline $d$, respectively, in year $y$.

$N_{LOCAL,j,y}$ is the number of documents with authors from the same country as the publisher of journal $j$ in year $y$.

$N_{ENG,j,y}$ is the number of English-written documents in the journal $j$ in year $y$.

$T_{j,y}$ denotes the total number of documents published in the journal $j$ in year $y$.

Note: Documents by authors from multiple countries are fully attributed to each country, i.e. $T_{j,y} \neq \sum_c N_{c,j,y}$.

E-mail: vit.machacek@cerge-ei.cz

Vít Macháček has worked at the Institute for Democracy and Economic Analysis (IDEA) since 2015. He obtained his Mgr. degree from the Institute of Economic Studies at Charles University in 2016, where he is currently pursuing his Ph.D. Until 2018, he also worked as a Macroeconomic and Finance Analyst at Česká spořitelna. Vítek's research interests include the Economics of Innovation, Scientometrics, and European Integration.

E-mail: martin.srholec@cerge-ei.cz

Martin Srholec obtained his Ph.D from the Faculty of Economics at University of Economics and the Centre for Technology, Innovation and Culture at the University of Oslo. Since 2010, he has worked as a researcher at CERGE-EI in Prague. Between 2011 and 2017, he also worked at the Centre for Innovation, Research and Competence in the Learning Economy (CIRCLE) in Lund. Martin has worked at the Institute for Democracy and Economic Analysis since 2013. His research interests include Economics of Innovation, Innovation Systems and Innnovation Policy.

Unfortunately, this website is not suitable for low-resolution screens. We recommend reading on desktop, laptops or tablets at least. Reading on smartphones is prohibited as the screen is simply too small.

This application is optimized for laptops and desktops. Errors may occur on smartphones, tablets and other devices. We are sorry for any inconvenience.

ARE MY BITCOINS SAFE